Context:

A G20 meet was held recently to discuss sustainable ways to harness ocean resources.

Ocean Resources:

Blue economy:

Components of Blue economy:

Components of Blue economy:

News Source: The Hindu

- The living and nonliving resources found in the ocean water and bottoms are called “marine resources.”

- Marine resources are the living and nonliving things that can be found in the ocean’s water and on its bottom. These resources, which include marine water, are called marine resources.

- Biotic Resources: The oceans’ biological resources include fish, crabs, mollusks, coral, reptiles, and mammals, among others.

- Planktons: Zooplanktons and phytoplankton are microscopic organisms that float to the surface of the water. The microscopic foraminifera, radiolarians, diatoms, coccolithophores, dinoflagellates, and larvae of several marine animals, such as fish, crabs, sea stars, etc., are a few examples of planktons.

- Nekton: The animals that are actively moving in the water are considered nekton. Examples include invertebrates like shrimp and vertebrates like fish, whales, turtles, and sharks.

- Benthos: The organisms that make up the benthos are those that are biologically connected to the ocean floor. Echinoderms, crustaceans, mollusks, poriferans, and annelids make up the majority of the benthos.

- Abiotic resources of the ocean refer to non-living natural resources that can be found within the marine environment.

- They are broadly classified as mineral resources and energy resources.

- Minerals dissolved in seawater: Certain minerals are present in small quantities within seawater itself and can be extracted using specialized processes.

- Continental Shelf and Slope Deposits: These deposits are found on the shallow seabed regions, primarily on the continental shelves and slopes. For Examples: Diamond, Fisheries Sector, Pearls, Monazite sand, a source of thorium, found off the Kerala coast.

- Sediments on the deep ocean floor: Nodules of manganese contain a variety of minerals, including lead, zinc, nickel, copper, cobalt, and copper.

| Wave Energy: |

|

| Tidal Energy: |

|

| Ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC): |

|

| Offshore wind energy: |

|

| Natural Gas: |

|

| Clathrate Hydrates: |

|

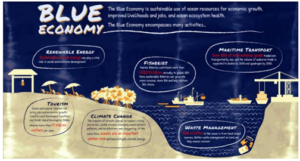

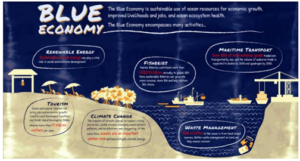

- As per the World Bank, the blue economy is defined as “sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and jobs while preserving the health of the ecosystem.”

- The blue economy comprises a range of economic sectors and related policies that together determine whether the use of ocean resources is sustainable.

Components of Blue economy:

Components of Blue economy:

- Fisheries and Aquaculture: Sustainable fishing practices and responsible aquaculture contribute to food security, employment, and income generation.

- Maritime Transportation and Shipping: The shipping industry plays a crucial role in global trade and connectivity.

- Tourism and Recreation: Coastal and marine tourism can stimulate local economies if overexploitation and environmental degradation are avoided.

- Renewable Energy: The blue economy includes the development of renewable energy sources like offshore wind, wave, and tidal energy, reducing dependence on fossil fuels.

- Coastal Development: Sustainable development of coastal areas involves balancing human activities with conservation efforts to protect marine ecosystems.

- Overfishing: Fish population is being depleted faster than the rate of replenishment. This not only disrupts marine ecosystems but also impacts the livelihoods of coastal communities reliant on fishing.

- Pollution and marine debris: Pollution from industrial waste, agricultural runoff, plastic debris, and oil spills adversely affect marine life, degrade habitats, and disrupt the entire marine food chain.

- Climate change impacts: Rising ocean temperatures, sea level rise, and ocean acidification due to climate change pose serious threats to marine ecosystems and coastal communities. Coral bleaching, habitat loss, and shifts in species distribution negatively impact fishing and tourism industries.

- Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing: IUU fishing undermines sustainable fisheries management by bypassing regulations and quotas, posing risks to fish stocks and the livelihoods of legitimate fishers.

- Sustainable Technologies: Developing sustainable technologies for ocean exploration and resource extraction is expensive and risky. Striking a balance between innovation and environmental concerns is essential for the blue economy’s success.

- Limited technology and infrastructure: Many coastal and developing regions lack the necessary technology and infrastructure to fully capitalize on blue economy opportunities, such as adequate port facilities, maritime transportation, and monitoring systems for sustainable resource management.

- Inadequate data and information: Sound decision-making in the blue economy relies on accurate and up-to-date data on ocean resources and ecosystems. Gaps in data hinder the formulation of effective policies and strategies.

- Coastal erosion and habitat loss: Human activities like coastal development and dredging contribute to habitat loss and erosion, severely impacting critical marine ecosystems like mangroves, salt marshes, and coral reefs.

- Collaboration among nations: The sustainable management of ocean resources will require collaboration across borders and sectors through a variety of partnerships which is particularly challenging for Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) who face significant limitations.

- Environmental sustainability: The blue economy concept seeks to promote economic growth, social inclusion and preservation or improvement of livelihoods while at the same time ensuring environmental sustainability. So, to build a blue economy, sustainability needs to be placed at its center.

- Interlinkages: It needs to be ensured that policies do not undermine each other and that interlinkages are leveraged for the benefit of people, planet and prosperity.

- GDP: India’s blue economy accounts for roughly 4% of the GDP and is estimated to increase once the mechanism is improved.

- Fisheries: India is the second largest fish producing nation in the world and has a fleet of 2,50,000 fishing boats.

- Minerals: India has been granted exclusive rights to explore polymetallic nodules in the Central Indian Ocean Basin. It has explored four million square miles and established two mine locations since then. This contract was initially signed on 25th March 2002 for a period of 15 years, which later was extended by the authority twice for 5 years period, during 2017 and 2022.

- Coastline: India has a marine position with 7,517 kilometers of coastline. Nine of India’s states have access to the coastline.

- Shipping Industry: Modal share of coastal shipping has the potential to increase to 33% by 2035, up from roughly 6% presently.

- Oil and gas trade: Most of the country’s oil and gas is supplied by sea, leading to the Indian Ocean region being critical to India’s economic growth.

- Global economic corridor: The Indian Ocean’s Blue Economy has become a global economic corridor. It is the world’s third-largest body of water, covering 68.5 million square kms and rich in oil and mineral resources.

- Resource inventories: Under the schemes “Ocean—Services, Modelling, Application, Resources and Technology (O-SMART)” and “Deep Ocean Mission (DOM)” of MoES, resource inventories for energy, fisheries, and minerals have been taken up.

- Exploration of Polymetallic Nodules: Government of India has been given rights for exploration of polymetallic nodules from the Central Indian Ocean Basin (CIOB).

- Seabed is known to contain polymetallic nodules, polymetallic sulphides, and cobalt-rich manganese crusts.

- India’s estimated polymetallic nodule resource potential is 380 million tonnes, containing 4.7 million tonnes of nickel, 4.29 million tonnes of copper and 0.55 million tonnes of cobalt and 92.59 million tonnes of manganese.

- These are critical for transitioning to a low-carbon economy that pivots on wind, solar and geothermal power. For instance, an electric car battery needs nearly 8 kilograms of Lithium, 35 kilograms nickel, 20 kilograms manganese, and 14 kilograms of cobalt.

- Inclusive Approach: According to the Sixth National Report (NR6) to the CBD, India is on pace to meet its biodiversity targets and has exceeded many of them with stronger inclusion of local communities, Indigenous peoples, and women in conservation activities. The 2017 Wetland Conservation Rules in India promoted the concept of “wise use,” which involves people in conservation.

- Preventing coral bleaching: The Coastal Ocean Monitoring and Prediction System (COMAPS) and Coral Bleaching Alert System (CBAS) are two measures the Indian government has done to save its coral reefs.

- Mangrove protection: To collaborate on the implementation of initiatives in mangrove areas, Andhra Pradesh has established eco development committees and Van Samrakshan Samithis.

- International Blue Carbon Initiative: “Magical Mangroves—Join the Movement” to combat climate change through the preservation and restoration of coastal and marine ecosystems underlines the importance of protecting mangroves

- Alliance for Blue Nature: It is an international collaboration with the goal of advancing Ocean Conservation Areas.

- GloLitter Partnerships Project: It seeks to assist the fishing and maritime transportation industries in transitioning to a post-plastic world.

- London Convention: A 1972 treaty on preventing marine pollution by the discharge of wastes and other materials.

- Global Programme of Action (GPA): It aims to protect marine environments from land-based activities.

- Southeast Asian initiatives: To balance coastal conservation and development with habitat and ecological protection, such as “blue infrastructure development” and “building with nature” techniques, are being adopted.

- One Health model: It unifies ecosystems, agriculture, wildlife, and urban environments into a single approach to the well-being of people and the environment.

- Biodiversity Vision 2050: The biodiversity vision for 2050 calls for the importance, preservation, restoration, and judicious use of biodiversity.

- UN’s 30X30 goal: safeguarding at least 30% of the earth by 2030.

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), 1982.

|

Post Views: 220